My Deep-Value Strategy Revealed

This is the story behind my businesslike deep-value investing approach.

Back in 2017, I was a financial trader working 15-hour days. I’d stare at screens waiting for market-moving news and wake up at 3am to check my positions.

I was tired.

I decided to do something that didn’t require so much work.

I’ve worked for myself since 2003 and have always loved business.

Owning a group of cash-flowing businesses while using the cash-flow to buy more, seemed a good way to go.

Even better, I wouldn’t have to sit in front of screens or wake up in the middle of the night to check on them.

I initially decided to acquire small-to-medium sized businesses and scale through bolt-on acquisitions and organic growth.

I’d finance the acquisition with cash and debt, serviced by the acquired business.

Nothing focuses the mind like having to pay off a huge debt by operating an unfamiliar business.

In this situation, there are only two things that matter:

The price you pay

The ability for the business to continue operating profitably

Unfortunately, most small businesses are mediocre and the owners (naturally) want top-dollar.

Finding deals was hard.

Actually completing deals was nearly impossible and a colossal waste of time.

Growing each existing business was also painfully hard work. Managing people and developing scalable products is incredibly challenging.

After a few years, I realised that this was not the way I wanted to operate.

So, I decided to do something different.

I just didn’t know what exactly.

The epiphany

The main goal hadn’t changed, I just needed a better strategy.

Then, one day, on holiday, I decided to look at the stock-market.

I went to a local café and fired up my laptop.

I couldn't believe my eyes.

I used the same mental framework I’d use to buy smaller businesses, privately.

I started with the balance sheet and then checked the income statement (for revenue) before taking a look at the free-cash-flow.

I thought I’d made a mistake…

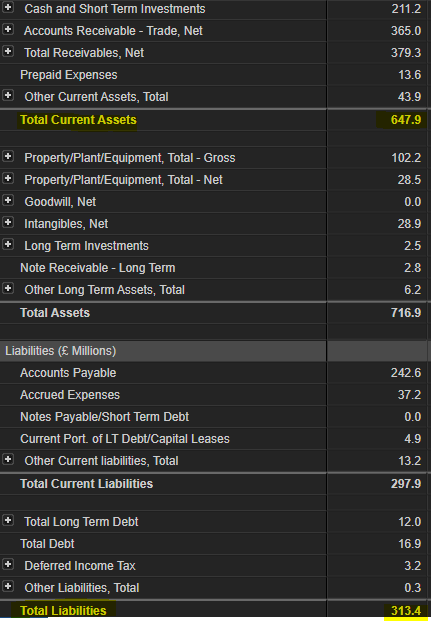

One of these businesses had a market cap of just over £200mn but their total current assets totalled almost £650mn.

The total liabilities were only around £300mn.

The net-cash alone was almost equal to the market cap.

I checked the revenue. Over the past 5 years the business averaged around £300mn annually.

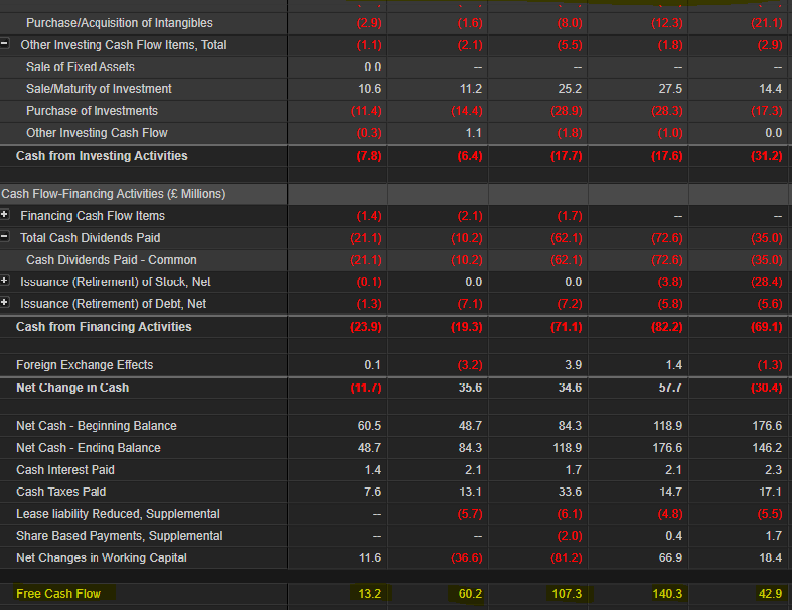

Finally, I had a look at the free-cash-flow. Over the past 5 years it’d averaged around £70mn per YEAR.

I needed a coffee to get things straight in my mind.

Here was a healthy, decent business on sale for roughly the price of its net-cash.

I’d then be getting the £70mn per year for nothing, for however long it continued to operate (it was already 40 yrs old).

Plus, I’d get the £100mn of non-current assets.

I laughed out loud to myself. I imagined making an offer like this to a small business owner in real-life.

The people at the next table nervously moved away.

I ordered another coffee and started searching for more.

It didn’t take long before I found another, similar business, with a flawless balance sheet and incredible cash-flow margins selling for just 3X its average FCF.

Then another.

I was simply looking for businesses that had net-cash amounts similar to the market cap.

There were hundreds of them listed all over the world.

I was hooked.

Not so fast

I’ve been around the block enough to know that if something seems too good to be true it usually is.

Why would decent businesses be given away like this?

There had to be a ‘catch’ and I couldn’t invest a penny until I understood what it was.

I started reading.

I already had a copy of the Intelligent Investor. I’d kind of half read it over the years but the main points clearly never entered my small brain.

This time, I read it again, with purpose.

Suddenly my experience made a lot more sense, but I was now hungry for more information.

I wanted case studies of successful investors who’d followed the same path.

I wanted to make sure I correctly understood the meaning of ‘market cap’ or there wasn’t some strange difference in how listed companies compile their financial statements.

Most of all, I wanted to make sure I wasn’t just an idiot that was about to pour all his money down the drain.

So I kept going. Books, blogs, podcasts, articles, interviews and anything else I could find.

It soon became clear that I was on to something.

The ‘catch’ is that most people aren’t patient enough to allow this type of investing to work its magic.

For me, patience and the ability to do nothing are, apparently, my superpower. Ha!

My natural inclination was towards ‘deep-value’ investing, because this is how I’d buy businesses in the real-world if such bargains ever existed.

It’d be like shooting fish in a barrel.

I’m not interested in predicting how the next 5 or 10 years will pan out.

So, I don’t bother.

Instead, I look for things that are so cheap, it jumps up and hits you over the head with a baseball bat.

I then make sure they’re not about to die and only allocate amounts that can’t kill me if they did go to zero.

I started with a small £50k account, to test the water. After a year or two I sold all my other businesses to focus exclusively on this one.

My business is still ‘buying and selling businesses’. I just do it via the stock market now.

My brokerage account is a business dealership and the market is my sole customer and supplier.

No people, no negotiations, no hassle. Just a buy/sell button and my trusty big-buttoned calculator.

My deep-value framework

I’m trying to compound capital as quickly as possible, without the risk of losing it all.

I understand the value of buying wonderful businesses at fair prices and holding for long periods.

But, for now, while I’m not burdened with billions of dollars, I’m just flipping cheap stocks.

This immediately excludes many different types of opportunity.

For example, I regularly see opportunities to make 20 or 30% returns.

Or stocks with a PE ratio of 14, which must be cheap because it’s half the other companies in the same sector.

I’ll also see people trying to figure out what a small company is going to do over the next 5 years.

They’ll share data and extrapolations about how the management team can ‘execute’ on the dreamy goals.

None of this interests me.

It’s either too difficult to pull off consistently (for me) or the margins are too small to justify tying up my capital.

I prefer to only buy things that have the potential to go 100% or more within the next couple of years.

I prefer to buy things that are cheap based on what they are right now rather than what I hope they will become.

When I find something cheap, I’ll often just watch it for a few months to try and buy it even cheaper.

I rethink each investment after around 3 years, on a case by case basis, to protect against opportunity cost.

My capital compounds for two reasons:

The performance dynamic of a group of cheap stocks

Company specific catalysts

My performance dances around like a kite in the wind with occasional boosts from individual stocks popping off.

It’s mind-blowingly consistent.

I believe this is down to the specific make-up of the individual type of stock I look for.

Asymmetric bets

Protection of capital is the number one priority.

I only invest into individual stocks that I feel provide an enormous margin of safety from multiple different angles.

I like stocks that are cheap to assets.

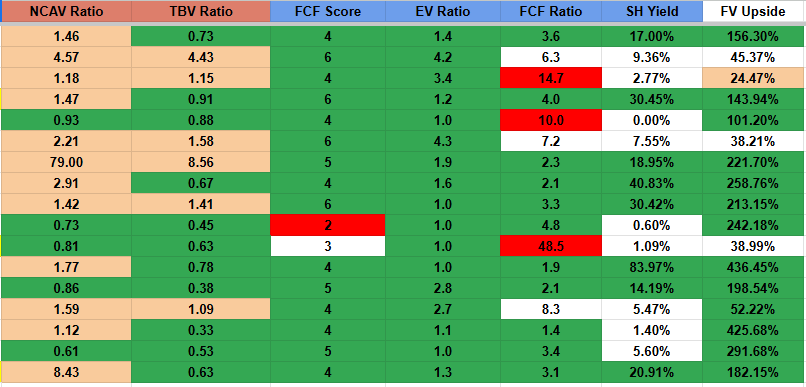

I have two main asset-based criteria that I look for:

Net-Current-Asset-Value (NCAV) ratio

Tangible-Book-Value (TBV) ratio

Finding stocks with a very low NCAV ratio is actually quite difficult, by the time you’ve weeded out all the cash-burning freaks shows.

They exist, and when I find them I load the boat, but in general, I prefer TBV.

There are more of them and TBV is still an excellent proxy for liquidation value if you only count the stuff that could be sold at an auction at fire-sale prices.

My favourite scenario is when a stock is trading so far below TBV that you could double your money without it even getting back to TBV.

A ratio of 0.3 or below is a nice sweet spot, especially if you ever find yourself relying solely on asset-value.

The problem with many cheap-to-asset stocks is that the earnings are pitiful or non-existent, relative to market cap.

To mitigate this, I search for those that also have solid relative earnings.

I use the 5Y average free-cash-flow figure as my baseline for earnings. I also look for the majority of years to be FCF positive.

This smoothes out the numbers and helps to find genuinely profitable businesses rather than those with weird one-off profits.

It also digs up hidden gems.

Often, the PE ratio will be exceedingly high because last year's profit has taken a hit.

But, overall, the business is a cash-machine that is going through some short-term struggles.

I use two main earnings metrics:

Enterprise Value to Avg 5Y free-cash-flow (EV/FCF)

Price (market cap) to Avg 5Y free-cash-flow (P/FCF

EV /FCF is my favourite, because I consider enterprise value the more accurate cost of buying a business in real-life.

However, the stock must be cheap from the perspective of both earnings measures.

This ensures the business is healthy and genuinely cheap from an earnings perspective.

The only real check required on these is into whether or not future earnings can be expected to continue as they have recently.

Sometimes, there is a specific reason why this is not the case and these need to be analysed and revalued based on the most probable future reality.

I once invested into a mining stock with strong historical earnings but the mine that generated those earnings was exhausted.

This was an example of something that required careful research before deciding whether it was still ‘cheap’ or just a value-trap.

The next indicator of a cheap stock is shareholder yield.

I base this on the total amount paid by the business for dividends and buybacks, versus the 5Y Avg free-cash-flow.

This tells me how much cash I could receive from a business if it gets back to ‘normal’ over the next couple of years.

A really high yield indicates that a decent quality business is being mispriced for some short-term uncertainty.

If my deeper research agrees, then these stocks offer multiple routes to generating excess returns.

It only has to resume an average level of profitability in order to deliver double digit returns, without ANY stock price movement.

A combination of these things maximises the margin of safety.

If earnings don’t recover you have the protection of asset value. If the market never recognises its asset-value, it will definitely recognise a return to normal profitability.

If the stock price never moves, I have the protection of receiving strong shareholder yield as the businesses profits revert to the mean.

Each stock is loaded with multiple reasons for the market to recognise the mispricing and rerate it.

A Silicon Valley Bro would probably call this a margin of safety stack.

Buying at such low prices also means that it’s difficult for each stock to keep falling. Every leg down, makes the next drop even more difficult to sustain.

Like an elastic band getting tighter and tighter as it's pulled lower and lower.

And, just like an elastic band, the explosive potential is all to the upside, when it’s eventually released from negative sentiment.

This is why we can reasonably expect 100% profits or more on each stock.

This is asymmetric betting.

A group of these bets make long-term outperformance almost inevitable.

(My portfolio, above, often contains a mix of stocks cheap from multiple angles).

Catching butterflies

One of my favourite sayings comes from Brazilian novelist Mario Quintana:

“Don’t waste your time chasing butterflies. Mend your garden and the butterflies will come.”

The same principle powers a deep-value stock portfolio.

Instead of searching for ‘catalysts’ and ‘entry-timings’ that will cause prices of stocks to rise, simply buy stocks that will attract catalysts.

The stocks I own have the following characteristics:

Lots of cash relative to market cap

No significant debt (negative net-debt)

Consistent and high levels of recent free-cash-flow relative to market cap

Simple, boring businesses that have been trundling along for decades

Significant assets that could be sold for cash if required

A price that is ridiculously low relative to the intrinsic value

I focus on these things because this is what I’d buy for my own real-world miniature business empire.

It feels natural to me and is very easy for me to keep doing consistently.

Cash is oxygen to a business and having lots of it makes everything comfortable, even in a crisis.

Especially in a crisis.

This provides a much higher chance of each business not dying AND reverting back to the mean of profitability.

Remember, this is all we need to make big gains in deep-value.

Aside from making me feel warm and fuzzy, these types of stocks also attract catalysts like butterflies into a flower garden.

For example:

A stock might have been trading for decades, but as soon as the price declines significantly, buyout offers often arrive within months.

It’s just rational to buy up competitor businesses when the price is objectively low. They simply can’t resist a juicy deal.

This is also a powerful catalyst for a stock to become rerated, based on the terms of the deal.

It’s amplified when they can pay for the cash and get everything else for free.

Another example is management themselves suddenly feeling like they must ‘do something’.

The stock price is down, everyone knows it's irrational, but the pressure can cause teams to take action.

This can be in the form of operational improvements, or a balance sheet clean-up or even a product investment.

These actions often lead to small improvements which generate huge gains from stock prices that imply the business is going to die soon.

Other actions include special dividends or buy backs. This is especially true from high-cash stocks like the ones I focus on.

I once bought a stock in the February and received an (unexpected) special dividend in the April, which yielded 43%.

It turned out that the management team did this regularly as cash stacked up on the balance sheet.

The average SH yield over 8 years (including all the specials) was over 25%.

But, no one knew about this. The price had fallen, but the business remained a cash-cow. The market simply overlooked it.

Of course, the biggest catalyst is the purchase price.

I can’t tell you how many times I’ve found a cheap stock, bought it and then had an unexpected catalyst occur, simply because it was so cheap.

Compounding wealth

When asked why everyone doesn’t just follow this type of approach to become wealthy, Warren Buffett once said:

“Because no one wants to get rich slowly.”

And, I suppose this is true.

But not for me.

I love this business and the consistency of the outcome when focused on these types of asymmetric bets.

If my capital becomes too big to flip, I’m keen to graduate to activist investing and buying whole businesses.

If not, I’ll continue enjoying the process.

Stock by stock, one asymmetric bet after another, the capital consistently grows and my business dealership trundles along.